My experience of a temporary scotoma (blind spot)

Aug 27, 2020, 9:21a - Consciousness

Last December I had a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It was quite serendipitous too, because I have been thinking about this medical condition and researching it for the past 5 years... So here goes.

Before I jump in and say what happened to me, I want to give a bit of background. It has been known for at least 150 years if ... more »

Read comments (10) - Comment

Poonam

- Aug 27, 2020, 10:34p

Very interesting. When you explained your new experiment to me you didn't share your personal experience. I am not surprised. It is a very keen observation on your part and a fascinating study of the visual cortex if you pursue it further.

It also reminded me of the old camaras that would blind you for a bit with their flash...although,I did not pay attention to what I saw after I was blinded and for how long.

Anyway sounds like a good experiment but please don't try it in yourself again...you have your mice for that.

Good luck!

Bharti

- Aug 31, 2020, 11:13a

Very interesting. This explains the feeling that at times I was oblivious to my surroundings. Good luck with your research and would be very interested in your findings

Ed

- Sep 1, 2020, 5:38a

Great to see this blog still kicking! I've been coming here for the past decade (mostly for the wormweb.org).

Elon

- Jul 3, 2021, 4:23a

Interesting blog mate, please consider to apply for neuralink , just checked your amazing track record on linkedin.

Kat

- Dec 11, 2022, 6:07p

I have visual field lossloss. Yep totally just unaware I'm missing vision now infact I forget even seeing a driver next to tyou, in the car was normal 4 yrs ago! Mine is permanent I have a refractory error. When faced with light stare at sun close eyes I only get the orange dots in remaining vision areas never lost one's. Note cerebral hemmorage and infarct py.

Cardinal

- May 7, 2023, 12:22p

I've also experienced this once a couple years ago, A small region of my eyesight just kind of disabled itself and I see how my brain was filling in the gaps, using the surrounding vision to assume what should be there. It lasted around 30 minutes and then faded away.

Someone

- Jun 11, 2023, 3:00p

This is migraine aura

Thoro

- Dec 16, 2024, 7:28a

I got the blurry thing. Spots that are blurry and flicker when blinking.

Kenton

- Jan 17, 2025, 5:38p

That’s a migraine my friend. I get 1 or 2 a year, if that and have for 20 years. Your description is just like I’d would describe.

fnfOzvSR

- Nov 8, 2025, 10:00p

1

Free will

May 16, 2014, 11:23p - Consciousness

As a conscious human, I feel as if I'm in control of my actions. When I'm considering what to drink with dinner and get a beer, that action is preceded by the conscious feeling of having made a choice. This contrasts with situations where actions are taken without any feeling of choosing: when I do something when I'm drunk, or ... more »

Read comments (3) - Comment

Marlon

- May 18, 2014, 11:40a

If free will is a feeling are there findings which support this, like the presence of endorphins or something? There should be some neurological changes that occur during isolated decision making in a controlled environment. One problem is how to correlate "a unit of decision making" as it happens in our minds... with anything physiologically - to me this is the problem a priori. Can we define a choice that is novel made in circumstances which are completely unknown, i.e. made by the individual and not programmed by your friends, parents, or Nabisco, for example.

If we could locate a novel decision point for said individual, then we could look to see if there are any "feelings" that can be measured, altered, induced (like pleasure, love, pain or hate) when the individual is presented with unknowns. My hunch is most people don't even really know when they are presented with unknowns, or to the contrary, when they have encountered the same set of choices before, and this feeling of having made a decision happens irregardless of the facts.

I look at determinism from a non-physical approach. People 99% of the time are completely unaware of the social conditions and training which have pre-empted our feeling of decision making. So there most certainly is "a feeling" that we have make decisions even though we haven't, even if science never finds any of the physical bio-markers. But this doesn't mean in the absence of pre-determined situations that some .1% of decisions aren't self-determined, it just means people follow predictable, or at least, traceable social patterns, principles, ideologies, ethical behaviors, most of the time. And when and if there are anomalies, we as decision feeling receptors, may not even be aware of either the time we are pre-determined, or of the time that we just defied the entire rule system.

Ultimately I think this oblivious feeling of decision making is a good thing for survival, as automatons it means we can break new ground without being aware of the risks or rewards.

nikhil

- May 20, 2014, 6:34a

Hi Marlon,

Good to hear from you. There is very little research on the mechanism of the feeling of free will. The most famous experiment on free will is one by Libet in the 80s. In this experiment, Libet measured an EEG signal that preceded a subject's decision to move their finger. This experiment suggested that brain events might precede the decision to act, at least in these narrow circumstances, and called into question the idea that we make decisions somehow independent of our brains. But there aren't any good studies of the molecular basis for the feeling of free will, as far as I know. It is generally difficult to measure molecular events in humans in real-time.

And like you point out, a lot of the decisions we think we're making independently are likely the result of social influences that we may have forgotten (e.g. advertising, cultural expectations).

Towards the end of your comment, you seem inclined to think that true free will might actually occur during some small fraction of the decisions that we make (e.g. 0.1%). But as I see it, determinism precludes even this. On what grounds do you think true free will can occur at all? Or are you simply referring to a more authentic feeling of free will only occurring a fraction of the time?

Ameya

- Nov 26, 2014, 3:10a

If I didn't know mushrooms were edible, I'd have never eaten one, ever. How many people are actually aware of freedom (to even think)? It is hard to handle. It is hard to even imagine. From a collective point of view, free will is possibly being supressed un-(collective-concious)ly (if that even exists, Mr. Jung!) for survival of the human species. From my personal experience, realizing that I am actually free is quite disorienting: to the extent of losing the meaning of life. A bunch of people going through the same existential crisis together , convincing 'true' freedom to the masses and being successful about it would be enough to disrupt a country's economy, I feel.

Consciousness as the only true emergence

Aug 9, 2013, 9:41a - Consciousness

As a neuroscientist obsessed with consciousness, I've spent the past 6 years in grad school grappling with what my philosophical point-of-view should be on the topic. I just read a new favorite, William Seager's Natural Fabrications (2012), and it has motivated me to write my current thoughts on a whole host of philosophical topics related to consciousness.

Since "consciousness" means ... more »

Read comments (5) - Comment

neha

- Aug 12, 2013, 1:37p

This was interesting. Thanks. Could you explain further why you dismiss #1, conservative emergence? What is "the difference between consciousness and the rest of physical reality"? Is it really true that consciousness has no externally visible effects which could be definitively distinguished from non-consciousness?

nikhil

- Aug 12, 2013, 5:47p

Neha,

Thanks for the questions. Let me try to answer them, the second one first.

No one today has any external test for consciousness. Even if you walk and talk and do fancy things only humans do, you could still (theoretically) lack internal experience. Think about people who sleepwalk - they behave seemingly in the absence of experience, as proverbial "zombies". There are even extreme cases where people do complicated things "in their sleep", like driving many miles, going into someone's house and killing them. So behavior alone does not seem to be sufficient to show the presence of consciousness.

On the flipside, behavior also doesn't seem to be necessary for consciousness. There are examples of people with "locked-in" syndrome who are completely paralyzed but eventually figure out a way to communicate to a nurse by blinking or changing the pH in their mouth. So even in the absence of behavior, consciousness can persist.

So there really isn't any definitive test for consciousness. If there was, we would hopefully be able to apply this test to other non-human creatures and assess their levels of consciousness. Then I could figure out if all this work with the worms had any chance of paying off, seeing as I don't even know if they're conscious or not!

Now on to the first question. The difference between consciousness and the rest of physical reality is that consciousness is an internal state (of experience), while the rest of physical reality is sufficiently encapsulated by external (observable) states (or so conventional science assumes). When matter affects matter, we can observe the change in various physical properties that occur. But somewhere in the chain, consciousness is produced, but this is different from the effect that matter was having on its surroundings in all the previous cases, because it can't be observed. So the hard question is how a physical state that lacks any internal states might build up into the complex internal state of consciousness. Science today has no way to bridge this gap between the physical and the internal (mental), and there's no clear path for how this can even be done.

Here's an analogy: making consciousness from matter is like making wine from water. If all you have is water and you can't add any other chemicals, you can never make wine. You can mix and cool and heat and beat it to your heart's content, but you'll never make wine. Similarly, I believe that no matter what you do to physical matter, you can never make consciousness in a conservatively emergent way.

Hopefully this explanation is clearer.

Alix

- Aug 30, 2013, 6:47p

Your blog post is super interesting. But faced with the four alternatives, I’m on the side of the reductionists. My main argument is simply that this is the most parsimonious explanation for how consciousness arises. It doesn’t invoke anything special. And I think one day we might be able to test for consciousness in simulated brains. Recent work in the group of Giulio Tononi developed an approach to measure the level of consciousness of patients in various states. By perturbing the brain and measuring its reaction patterns, they were able to discriminate patients that were awake, asleep, sedated or emerging from coma. Obviously this technique would only work with the human form of consciousness, but we could imagine creating a brain in a vat and looking for patterns of activity indicative of human consciousness. It wouldn’t be bullet proof because these patterns of activity could be associated with something else than consciousness, for example with something that always accompanies consciousness in humans, but not necessarily in a brain in a vat. But I think it’s a flaw to say that because we can’t currently test for consciousness, because it doesn’t have any external representation, it must be something special. They are presumably many phenomena that we can’t observe or test and yet it’s not a reason to invoke “radical” explanations.

Secondly, you write: “perhaps there is a basic law of consciousness, though it differs from known laws in that it operates at the macroscopic scale.” Is it possible that all laws exist at every scale, but that they only matter at a certain level? For example, from my understanding of physics, it’s not that the microscopic laws of physics don’t apply at the level of planets, but simply that they are not useful in understanding the global behavior of planets. Similarly, gravity exists at the microscopic scale, but is irrelevant. (I know that physicists are working on a unifying theory, yet one hasn't emerged yet.) Perhaps consciousness is similar in that it needs a complex enough system to become relevant. If this is true, then it’s not a fundamentally different property from all others.

nikhil

- Oct 30, 2013, 8:13a

Thanks for the comment Alix.

To your second point: I think you're confusing the concepts of things that matter *in practicee* with things that matter *in principle*. You say that though gravity exists at the microscopic scale, it is irrelevant. By this you mean that it is irrelevant in practice - you can forget about gravity and just model other forces and you get very accurate simulations. So gravity is only irrelevant *in practice*, but in principle it is still there and likely has a miniscule effect, but an effect nonetheless.

So I take this to mean that gravity is a microscale force that also manifests at the macroscale, but merely as the sum or combination of the microscales (as a conservative emergent).

So when you say that laws only "matter" at a certain level, again I think you're speaking *in practice*. In principle the laws of physics can be viewed as being generated at the microscale and then affecting all higher scales. What I'm concerned with is what is *in principle* plausible with respect to the generation of consciousness.

The in principle/in practice dichotomy often also includes another source of linguistic difficulty: what we're comfortable understanding. Often what is practical is also what is easier for human minds to comprehend, but that is not what I'm interested in here. Although the limits of understanding are inescapable, what I'm trying to understand is not a feature of those limits, but rather the real Truth that lies out there in the world.

Also, your second point towards the end seems to represent a belief in panpsychism - consciousness is there at all scales, but then "needs a complex enough system to become relevant", as you say.

Make up your mind! Are you with the conservative emergents (#1 in the text) or the panpsychists (#3)? To put it another way: do you thing that mind emerges from basic objective features of matter, or do you think all forms of matter have a little bit of proto-consciousness as a basic property?

I Am

- Dec 11, 2013, 7:52a

Perhaps Consciousness isn't physical? Any first member in a given series of subsequent members can only pass on what it itself possesses. If this is so, unconscious matter can't pass on consciousness. Perhaps I have it backwards!

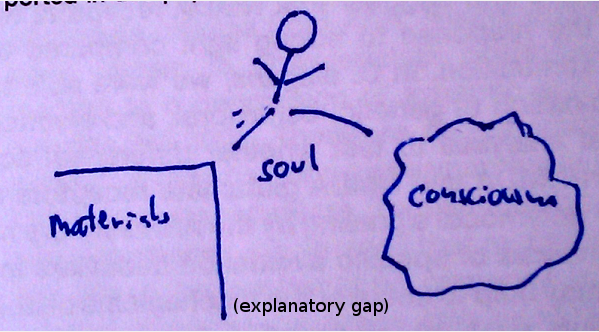

Countering a primitivist attack on the soul

May 1, 2013, 11:51a - Consciousness

I probably spend more time thinking about consciousness than any other topic or person (shh, don't tell Becca or my worms :). Previously, I described a simple argument for the existence of the soul, which formed the rational basis for my belief in the soul. My argument was that the existence of consciousness requires a non-physical explanation, so I ... more »

Read comments (11) - Comment

C. Elegans XIV

- May 1, 2013, 11:34a

I implore you, stop the genocide against my kind! In your quest to unravel consciousness, your methods have been crude and, ironically, quite primitive in nature. These supposed "experiments" have led to a widespread belief among my brethren: that sacrificial offerings to the Blue Eyed Sky God will end the peroxide plague. We both know this is untrue. This is your final warning.

rosa

- May 1, 2013, 12:29p

lol

Josh

- May 3, 2013, 8:03a

I assume I am not the "Josh" referenced in this post, because I do not hold those views. Instead, I like your previous argument, but only steps 1 and 2. Step 3 seems to ignore the possibility that a Theory can exist for "how consciousness can arise from the physical" but we are currently too stupid to conceive it. Thoughts?

nikhil

- May 3, 2013, 9:07a

Give me your last name or initial and I'll tell you if you're the Josh I'm thinking of :)

Right, we may be too stupid, and we may wise up some day and come up with a plausible physical theory for consciousness. Of all the counter-arguments to my original argument for the soul, that is what I would hold out for. But I'm not betting on it. My disinclination with this counter is that unlike other kinds of theories, there are basically no potential consciousness-arising-from-the-physical theories that people have come up with. It's not like we've had a bunch of theories, ruled them out one by one, and are waiting for more (which is the case for most conventional science - think of advances in our understanding of the causes of disease). Instead, we have exactly 0 theories, and so have nothing to test. This distinguishes the consciousness problem from other scientific problems.

The current common philosophical position with regard to nature is that all of nature could be understand as a very complicated series of physical events, none of which call for either the existence of consciousness or some functional consequence of consciousness. So the idea is that all of nature can be explained purely on the basis of observable causes and effects. Why aren't we all robots/zombies without consciousness? Yet we know we have consciousness (in fact it's the one most basic truth that we know, and all other knowledge resides on top), so clearly the standard objective science view is missing out on a natural phenomenon, something not objectively observable. So science is not as comprehensive as we might think/hope. Maybe what's wrong is that it can't even observe a non-physical natural object, consciousness.

CAN

- May 7, 2013, 9:09a

a (flawed) theory that leaves us waiting for more:

http://www.amazon.com/Phi-A-Voyage-Brain-Soul/dp/030790721X/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1367051074&sr=8-1&keywords=giulio+tononi+phi

Jason

- May 10, 2013, 1:47p

This is some fascinating stuff. I think about these things a lot as well. If you have not yet had a chance, check out the book "Proof of Heaven: A Neurosurgeon's Journey into the Afterlife." On the whole, it's not the greatest book in the world but the meat of it is stellar. It provides some great questions and dots to connect.

Jason

- May 10, 2013, 3:17p

Also, as examples of primitive properties in your argument, I would use the forces (electromagnetic, strong and weak nuclear forces, and gravity) since they truly are fundamental while particles can seemingly always be broken down - far beyond quarks to our current understanding. Despite this discrepancy, your point is clearly stated and understood.

rosa

- May 13, 2013, 1:13p

- I think some people use the word "fundamental" where you use primitive.

- On your argument for the soul: This is the argument that i thought was Chalmers-y: the transition from an epistemological claim about what we know right now (2) to an ontological claim about what the world is like (3). It's shady when he does it and it's shady when you do it! shady for reasons that josh mentioned in the comment - the absence of a current theory might be because we don't know enough or we're too stupid - it's not obvious that it means that there IS no such theory possible.

- On your primitivist counter-argument (PCA): this one goes the other way - from an ontological claim (2) - consciousness is a primitive property of the world to (3,4,5) which are basically about our explanatory practices. you could interpret this as basically throwing our hands up - fundamental facts don't admit of explanation because explanation bottoms out - but that's not very satisfying.

- I don't think your argument and this so-called counter-argument are opposed to each other. PCA (2) basically assumes your conclusion (3 in the original argument). (2), by saying consciousness is a primitive "like mass or charge" already assumes that consciousness is a distinct (non-physical) property.

- I don't find PCA (5) useful... what's the difference between appealing to an (unexplained, unexplainable) non-physical soul, and appealing to consciousness as its own primitive property? Appealing to the soul just pushes the mystery back a step, whereas primitivism embraces it. I don't see a meaningful difference between these two strategies... difference seems verbal - call it a soul or call it consciousness - who cares?

- "Each primitive property is associated with the most simple pieces of matter" - yeah... not sure the physicists would agree with you on this one... or the philosophers. there are lots of primitive properties that we can't really reduce to other properties. not all of them are small. some people think that the property of "being true" is primitive. what about the property of "being big"?

- "if you assume consciousness is a primitive property, than all matter, down to the quark, must have a small bit of consciousness to assemble into the whole seen in brains (akin to mass or charge)" - i don't see why we have to say this. consciousness is primitive, it is associated with something big instead of something small. something can be big without all of its constituents having some property of "bigness" that then adds up...

- On conclusion (A) - again, chalmers basically thinks this (he calls it pan-proto-psychism) BECAUSE of an argument very similar to your original argument. so i don't think these are opposed to each other. Although pan-proto-psychism can be interpreted as a form of physicalism/materialism, if we just suppose that proto-psychism is just another physical property ... and when it's put together with other things with physical properties in the right way, we get people and animals and consciousness.

- "... all other phenomenon which are reducible to particle-scale components." wtf really? this is like .. cowboy reductionism at its worst! i'm not convinced anyone really believes this. want to ask you to read Dennett's "real patterns".

- "Emergence as a philosophical position seems implausible to me given the ridiculous explanatory success of reductionism." - yeah, I don't buy this. interpreted weakly, emergence and reductionism are not incompatible, and lots of things are emergent - complex biological properties, wetness, chemical properties.

- Response to your comment: wow - this part sounds kind of like Nagel's newest - mind and cosmos. science is dramatically inadequate, etc. not just for explaining consciousness but to explaining LIFE (living things in nature, conscious or otherwise). i think i've said this before, but i think that if you're not bothered by our inability to reduce LIFE to physics, then you shouldn't be bothered about consciousness either - they are fundamentally the same kind of problem. The people who think that there must be some non-physical basis to consciousness are just like the vitalists from the turn of the century who thought that there had to be some non-physical basis for life: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vitalism

http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/reduction-biology/

[this comment was copied from an email between Rosa and Nikhil]

nikhil

- May 13, 2013, 1:16p

Cool. Thanks for the detailed response.

I think I've heard several of your comments before, and I think I have reasonable counters. Let's see how convincing you find them:

* I use the word "primitive"because this is the word a computer scientist would use. In computer languages, there are things called "primitives", which are objects that are irreducible. For example, integers and characters are considered primitives in C, whereas a word (string of characters) is not, because it is simply built from the character primitive.

* I agree that the transition from what we don't understand to making a claim about the world is very, very shady. It's the same as "Absence of evidence is not evidence of absence." But I think consciousness is special here. It's special because no theory has ever been able to really explain it. Usually in science we have lots of plausible theories that we rule out until we find the best (most true) one. The earth being the center of the universe was reasonable: when we looked up it looked like the stars rotated around us. But then we got new evidence (or looked at existing evidence with greater analytical skill) and we generated a new theory for our planet's place in the universe, where we rotate around the sun. Both explanations are plausible, even if only one is true (or more true). The problem with physical theories of consciousness is that none of them really explain why consciousness exists. Tonini's phi theory is a current example: interesting analysis, but nothing he suggests necessitates the existence of consciousness from pure objective stuff. And no theory ever has, as far as I know. So I'm inclined to be a bit shady, because our situation with consciousness is different than any situation we've had with explaining other objective phenomena, including life (more on that below).

* I agree that having consciousness be a fundamental property is very unsatisfying. I'm open to better ideas.

* I'm confused when you write "PCA (2) basically assumes your conclusion (3 in the original argument). (2), by saying that consciousness is a primitive "like mass or charge", already assumes that consciousness is a distinct (non-physical) property." I guess I don't think of mass or charge as non-physical properties, do you? I think of them as fundamental physical properties that must be accepted (though I'm not up-to-date on my particle physics). So I guess I'm not understanding what you're trying to say here.

My difficulty with accepting consciousness as a fundamental property is that it seems to happen on a more macroscopic scale than other fundamental properties. So consciousness is somehow different.

* On "call it soul or call it consciousness - who cares?" I think this is a good point - what do we get by saying that there's something non-physical underlying consciousness? Since this is so mysterious as well, does it buy us anything by pushing the mystery of consciousness to a new, mysterious domain? I'm not sure, but I feel that it somehow does. Let me try an analogy: Let's say you're trying to build a treehouse, but all you have are sugarcubes of all imaginable shapes and sizes. So you build it, and it rains and dissappears. So then you think, I just need a roof to keep my treehouse from dissolving. So you build a roof of sugarcubes, but then it rains, and though it takes a little longer to dissolve, it all dissapears anyway. You really need to build your treehouse/theory out of some different material, even if you know nothing about that material. Lumber shows up one day on your front porch, and you use it, and now your treehouse survives the storm. You've never seen lumber before, have no idea what it's made of or how it works.

This is a bit of an overly creative analogy. But I guess my point is this: if your current system of thinking is unsatisfactory, it's worthwhile to devise a new plan that relies on something outside the current system. I'm not sure what this buys us, except for one small step in (perhaps) the right direction.

I think this might be the weakest part of my argument.

* I think all physical properties can be reduced and explained in terms of smaller properties, until you get to the fundamental properties. This is super-reductionism. I struggle to think of an example (outside of consciousness) where this is not true. "Being true" is a conceptual property that is a purely the product of the mind which can think untrue things - it's not a fundamental property like mass or charge. "Being big" is again a conceptual property, solely the product of the mind and without existence in its absence.

* Again, "bigness" is a conceptual property - it's not a property of the physical world in the absence of a mind. At the very core, I believe all matter interacts first at the lowest level, and that bubbles up to higher levels of analysis that our minds have greater ease thinking about or observing.

* I've alway had some affinity to Chalmers and Nagel, though I have difficulty with this pan-psychism position, which to me just seems intuitively absurd.

* I guess I'm a "cowboy reductionist". I always wanted to be a cowboy :) I do believe this. I will look at Dennett's paper you cite, which I haven't seen before.

* I agree that if you take a weak interpretation of emergence, it is compatible with reductionism. But that's not the interesting interpretation, as emergence doesn't really buy us anything except for some psychological ease (of not trying to think of all the many lower-level interactions that are occurring). It buys us abstraction, but especially in the world of biology abstraction can be very misleading, so I prefer to avoid it when I think it's going to impede truth-finding. With the examples of emergent properties you cite (complex biological properties, wetnness, chemical properties), are you taking the strong anti-reductionist view of emergence, or the weak one?

If you can tell me one truly emergent phenomena that is anti-reductionist, I'm all ears. If not, either consciousness is special in this regard, or you have to believe that it's a fundamental microscopic property, or that it can be generated from other fundamental properties like mass and charge. Maybe I just have to accept that the latter is the truth and forget about the immaterial "soul". But even that remains mysterious.

* I didn't know about Nagel's new book - I'll check it out. Does he really argue that science has not explained life? That's ridiculous if he does. If he does, I wonder how he defines life, as I guess you could make an argument against science's success if you confused life with consciousness.

The argument you make is very common, but I disagree. Life can be defined in a functionalist way: a thing that grows, metabolizes and reproduces is considered alive. There are some edge cases that are confusing (e.g. viruses), but we'll ignore that. With this objective measure of life, it became clear with advances in reductionism techniques (molecular biology and biochemistry) that all of these functions could be implemented by proteins, lipids, sugars and nucleic acids. So life has been solved. I'm very familiar with vitalism and I agree it's hogwash. But I disagree in saying that the problem of consciousness and the problem of life are the same. Life can be objectively defined, but what makes consciousness special is that it seems to elude objective definition because it is fundamentally about internal experience. Life is just like any other objective phenomenon that science has tackled or will tackle. Consciousness is special because it isn't obviously an objective phenomenon, so parallels are not easily drawn from past successes.

I'm hopeful that we will we find the properties of neural circuits that underly consciousness. But the hard problem of explaining why they produce this whole new domain of phenomenon at all will remain.

Alright, I feel like I've addressed all you wrote. If you have it in you I'd enjoy reading a response.

rosa

- Jun 15, 2013, 3:23p

on life - i think once you accept the functionalist understanding of what life is, you've moved away from the original vitalist question (which still can't be answered) and declared yourself satisfied with the answer to a *different* question, which it now seems the right one to ask. (i.e. the original question no longer seems interesting). I think accepting a physicalist/functionalist theory of consciousness is similar, except that you are unwilling to discard the original question in the mind case.

on "consciousness is a primitive like mass or charge" - i took that to mean that consciousness is PRIMITIVE in the way that mass and charge are, but not PHYSICAL in the way that mass and charge are (and so in that way UNlike). that is, it is a primitive alongside physical primitives, but not itself a physical primitive.

wolf

- Aug 6, 2013, 4:17p

Your idea that (A) Consciousness is a primitive property and so every particle has some minimal quantum of consciousness. The consciousness we experience is some special configuration of these quantal consciousnesses arranged in our brain.

Is called Panpsychism and is being worked on an increasing number of people. The key is the recognition that what you see in front of your nose is an internaly generated phenomena. The pendulum is swinging back to this view although I hope we will not throw out the baby with the bathwater in rejecting materialistic science as a world view

Let's start with a definition

Aug 10, 2012, 10:05p - Consciousness

My main intellectual interest is to understand how the brain creates consciousness. When I tell this to people, they usually respond with "What do you mean by 'consciousness'? How do you define it?"

Human consciousness is certainly complex, but I think of it as being composed of 3 smaller parts, arranged in a hierarchy. The most primitive part of human ... more »

Read comments (6) - Comment

TomN

- Aug 12, 2012, 12:03a

If you haven't read "Second Person, Present Tense" by Daryl Gregory, I highly recommend this SF short story.

You can find a copy via the Internet Archive:

http://web.archive.org/web/20100114004527/http://www.asimovs.com/_issue_0702/Secondperson.shtml

The author's notes are an interesting post-read:

http://www.darylgregory.com/stories/SecondPersonPresentTense.aspx

It is just Science Fiction and it's a few years old now, but you might enjoy it.

nikhil

- Aug 12, 2012, 10:49a

That's a neat story Tom. Thanks for that.

Another way to think of the 3 facets of consciousness is:

* Step 1 = Perception : "Stuff is happening."

* Step 2 = Self : "Some of the stuff that is happening is happening to me."

* Step 3 = Free will : "I have control over the some of the stuff that is happening to me."

Raja

- Aug 13, 2012, 12:14p

"If we seek to understand ourselves, we must first understand the physical basis of consciousness."

Is this true? Might it be enough to have a working, descriptive understanding of how consciousness manifests itself, i.e. how we humans tend to interpret and relate to our notion of consciousness? Is it necessary to get answers to its physical underpinnings in order to live a meaningful life?

Put another way, how would having answers to the questions you are posing change the way you live or interpret your existence? It's fine if you just happen to be interested in thinking about and trying to find answers to those questions, but it's a much stronger claim to say that getting answers to these questions is somehow "important."

Somewhat related question (via the late philosopher Richard Rorty): Can you hypothesize a potential answer to the questions you've posed that would be satisfying and coherent? For most questions we ask about the world, it's usually pretty easy to give an example of a coherent answer even before doing any investigation. It's then possible to do research and test hypotheses that are based on our a priori "guesses".

It's not entirely clear what those testable hypotheses would even look like with respect to the most difficult questions surrounding consciousness (e.g. free will), but I am curious to hear what you think and what the current take on that problem is within the neuroscience community.

nikhil

- Aug 14, 2012, 6:56a

Good to hear from you Raja!

Alright, let's start at the beginning. In general, I think either I haven't been clear or you've misunderstood me. My quote:

"If we seek to understand ourselves, we must first understand the physical basis of consciousness."

I am definitely no trying to imply that it is necessary to answer the question of consciousness to live a meaningful life. Clearly no one has a satisfactory answer to this question but clearly loads of people live meaningful lives (or have meaningful aspects to the lives they live). I think we're debating 2 kinds of "understanding" - the first one (which I think you're talking about) is at the descriptive level. Take another phenomenon, let's say flying. When humans wanted to understand flying, it was totally reasonable to begin by surveying birds and floaters in the wind and other things that naturally flew. Describe them, describe their body plan and anatomy, their colors, and any other descriptive attribute - when they flew, for how long, from where to where, etc. With this compendium of knowledge, it's possible to predict whether new objects would fly or not (inference), and also to build something that flew (perhaps some of those fast-flapping lightweight bird-looking toys fall into this category). But I would say that this level of understanding remained superficial, even though the total bulk of knowledge was huge. To really understand flight more generally, I think you had to understand certain concepts, such as lift and how differential air pressure supports flight in the shape of wings. This second kind of understanding follows from the first, but the first alone is not satisfactory in my opinion, though necessary for getting to the second. This analogy can also be applied to the field of medicine and how a molecular understanding of diseases is a much less superficial understanding than a symptom-level kind of understanding. This is the epistemology of reductionism.

This quote is definitely not meant to have much existential power - think of it more as "if I want to get past the superficial and really get a better flavor of consciousness, I've got to start thinking about the mechanisms that underly it. I have to physically dissect it." As far as we can tell consciousness should have a physical basis, so other kinds of dissections (e.g. psychological, metaphysical, behavioral) may be interesting and helpful, but they won't get at the heart of the matter, so to speak.

This is not meant to be depressing or have any emotional content. It's just meant to be a statement of fact.

I only think the basis of consciousness is "important" if you care about consciousness - most people I talk to don't think about it at all. So for them it isn't important. But if you happen to be one of the few who are interested, I think it's important in the sense that if you want to be a good doctor, understanding the molecular basis of your patients' ailments is important. It's not the whole story and many other pieces also need to be there, but without it there's a huge gap in the work.

On to your "what would a potential answer even look like?" question. Again I guess I wasn't clear enough in my writing. For the question, "How does certain parts of the brain create consciousness", I don't think there is a possible answer, and I agree with you. I likened that to asking "How do positive and negative charges attract?" or "How does mass generate gravity?" These are questions about the properties of objects, properties which ultimately form a sort of ground truth. Even if I answer those questions I could always ask how the answers exist and just move the question one level down, forever. At some point I just have to accept that there are objects with specific properties, and go from there.

So the motivating question is clearly "How does the brain create consciousness?" but I'm willing to accept that consciousness is just a property of the brain. It's like saying that objects which have the properties X, Y and Z will also have the property of consciousness. What I'm now interested in, and what I think is scientifically tractable, is to figure out what the properties X, Y and Z are. Ideally, these properties would be both necessary and sufficient for consciousness. We know that some parts of the brain clearly play more important roles in consciousness than other parts, and I will write about one example in a later post. Why does part A of the brain have a role in consciousness while part does not? What makes these 2 parts, though sitting right next to each other, different in relation to consciousness? Is it what other parts they're functionally connected to? The way in which they're connected? Posed this way, the question becomes one of comparison, and comparing things is what science is all about (experiment vs. control).

I hope this long-ish comment clarifies. I'm also primarily focused on the question of perception, not of self or free will, so my comments above are directed at that aspect of consciousness.

The goal now is to find those neural differences that make the difference between conscious experiences and unconscious ones.

Andy L

- Aug 30, 2012, 11:45a

Great post! Looking forward to see where you are taking this!

Gokul

- Oct 14, 2012, 11:05a

Another wonderful post! Looking forward for the rest in the consciousness series!

The end of visual deprivation

Aug 2, 2011, 7:34a - Consciousness

It's the first day, morning, after opening my eyes after 7 days of visual deprivation. I opened my eyes last night, first in a dark room right after midnight, and then we lit a candle.

The first thing that's very striking, even in the morning now, is that everything that's blue looks extremely BLUE. Either I forgot what blue looked ... more »

Read comments (5) - Comment

Mike

- Feb 29, 2012, 10:53p

Wow, congrats on finishing the week! I have been considering doing the same thing and came across your page. How long did it take for your focus to go back to normal and the dizzy feeling to go away? Same day? Did you ever go back to that library to see if you could recognize anything?

nikhil

- Mar 10, 2012, 10:53a

Hi Mike,

Glad to hear you're also interested in doing something like this. If you do it, I'd love to hear about your experience.

My eye focusing was pretty bad right when I opened my eyes that night, but in the morning when I walked around my neighborhood it was pretty fine. The dizzy feeling also subsided by the middle of the next day or so.

One thing I didn't write about is that I got into a pretty serious bike accident when I biked into the lab that morning. I tried jumping a small curb which is normally no problem, but my timing was way off, I jumped too early, landed, and then my bike hit the curb. I flew over the handlebars and landed on my face and hands. I felt concrete scrape under my 2 front teeth. All in all, I was pretty banged up and chipped a bone in my wrist (first broken bone of my life). Everything healed up fine, but the point is that the hand-eye timing may take a while longer to get synchronized again.

I haven't gone back to the library yet. I should.

Olivia

- Jun 23, 2013, 4:48p

Great job on the experiment! I was wondering, if visual deprivation even for just a few hours can improve someone's eyesight (did I get that right?), is that a permanent effect or is it just temporary? If it is only temporary, how long do you think the effects of having an improved vision will last? Lastly, if the effects are temporary, do you suggest that I do visual deprivation regularly just so I could prolong the experience of an improved vision? Thank you and I hope to hear from you soon! I hope this improves my vision especially at night since I have a hard time seeing at night... I think it's something called night blindness

nikhil

- Jun 24, 2013, 6:20a

Hi Olivia,

I don't think the right way to think about the effect was visual deprivation had on me was to improve my vision. It did make me very sensitive to depth and color perception, but I don't think it improved my acuity or night vision. You could try it to see for yourself. Also, I think each episode of deprivation might need to be pretty prolonged, perhaps 1-2 days at least.

Olivia

- Jun 26, 2013, 5:52p

Alright! I will definitely try it for a day. I tried it for an hour and I ended up falling asleep. Thank you so much :)

Visual deprivation: Days 6 and 7

Aug 1, 2011, 12:51p - Consciousness

[For background, see my first post on the experiment. This is a rough transcript of a dictation made on day 7.]

It's T minus 11 hours. After talking to Sachin yesterday [day 6], he had a good idea to slowly introduce light back to me eyes, like starting with a candle or another single light source and then maybe ... more »

No comments - Write 1st Comment

Visual deprivation: Day 5

Jul 30, 2011, 11:31p - Consciousness

[For background, see my first post on the experiment. This is a rough transcript of a dictation made on day 6.]

Today was an interesting day. Very nice weather. I'm still pretty lethargic, I took a 2 and a half hour nap, but so did Becca so I'm not sure if it's due to my experiment.

It was Jude's ... more »

No comments - Write 1st Comment

Visual deprivation: Day 4

Jul 29, 2011, 11:32p - Consciousness

[For background, see my first post on the experiment. This is a rough transcript of a dictation made on day 5.]

It's a beautiful day (referring to day 5). Right now I'm sitting in the sun, without a shirt on. It's quite nice. Boris (my tortoise) has emerged from his little borough. He didn't come out yesterday but he ... more »

Read comments (3) - Comment

Liz Dzeng

- Aug 6, 2011, 5:43p

Hey Nik! Wow, I'm so impressed that your doing this. It sounds incredibly hard with a huge amount of self discipline required. I could not even last an hour I bet if I tried. I've really enjoyed reading your posts which are so descriptive and introspective. You really should publish these findings in a scientific journal, so few experiments have been done on this. I'm really interested to read about your "unmasking"!

Niniane

- Aug 23, 2011, 1:14a

Are there any more entries??

fnfOzvSR

- Nov 8, 2025, 10:13p

1

Visual deprivation: Day 3

Jul 28, 2011, 10:09p - Consciousness

[For background see my first post on this experiment. This is a rough transcript of a dictation made on day 4.]

I sort of just feel like I'm a puddle of mud. I sort of just feel like I would behave if I'm sick, cause I don't really do much and I just lie around all day. So it ... more »

Read comments (1) - Comment

Yu-li

- Aug 6, 2011, 6:57a

I like your introspective description. You really did something hard. I don't want to try that even though I wonder how it feels like.

About construction of space, I think measure theory can be helpful. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Measure_theory) Even without visual information, it must be possible to construct mental space of things as we have information on spatial order of things. I think what matters is (mental) metric (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metric_%28mathematics%29).

Visual deprivation: Day 2

Jul 27, 2011, 11:13p - Consciousness

[For background see my first post about my blindness experiment. This post is a rough transcript of a dictation on day 3.]

Yesterday I had a little bit of an adventure. I went around the block by myself. It's amazing how much I do not walk in a straight line. With cars going by on the street, it's amazing ... more »

Read comments (5) - Comment

Kanika

- Aug 5, 2011, 4:40p

I don't know if you did this already - bit about three years ago a movie came out- beautiful movie about the blind- called BLACK by Sanjay leela bansali staring amitabh.... I must watch it!!!

Yu-li

- Aug 5, 2011, 7:41p

Interesting. Your experiment tells that normal sense of distance greatly depends on visual information.It must be specific to visual sense. Physically, other types of information are not very sensitive to distance I think (They are not linear. I mean, the strength of scent depends on both distance and quantity for example). I am sorry that my description is not very accurate.

Good luck!

Niniane

- Aug 5, 2011, 9:05p

This is an awesome story. I like all the details of how you're watching Teen Wolf, etc. It sounds domestic and pleasant.

mom

- Aug 12, 2011, 1:16p

good reading your descriptions and findings son. Yes, the Indian movie 'Black' suggested by Kanika is wonderful and maybe you would be able to appriciate it. Netflix should have it.

sakshi

- Aug 24, 2011, 8:45p

hmmm.. ive been out of the loop !!! just got back in.. another thumbs up for black !!!

Visual deprivation: Day 1

Jul 26, 2011, 11:07p - Consciousness

[All posts in this series have been backdated to the date they occurred. For background info on my visual deprivation experiment, see my first post on the topic. This post is a rough transcript of a dictation I made on day 2.]

I started Monday night (last night) at midnight. Becca taped stretched-out cotton balls over my eyes, couple pieces ... more »

Read comments (6) - Comment

Nicky

- Aug 5, 2011, 7:57a

Did a desire to rip off the eye mask emerge after a few days? Did it just take longer than food deprivation or isolation? I am on the edge of my seat waiting for the next post!

nikhil

- Aug 5, 2011, 10:07a

Nope, a desire to rip off the eyemask and open my eyes never emerged, certainly nothing like the desire to eat after food deprivation or the desire to breathe after air deprivation.

Howard

- Aug 5, 2011, 10:53a

well, those are interesting comparisons because one could argue that the other two forms of deprivation you use for example are tied to very real needs of survival on a biological level. While food is a little different because given your survival school mean experiment you weren't lacking nutrition just variety and craving. With air deprivation, that's entirely different, no air = no life and your body starts to react involuntarily. so the one easy conclusion is that vision is not tied to survival instincts

nikhil

- Aug 5, 2011, 1:05p

Howard, I completely agree. I also think it's interesting to think about the brain basis for each of these deprivations. Vision is believed to rely mostly on the outer parts of the brain (the cortex), whereas more basic body functions like breathing and perhaps even hunger lie deeper in the brain. Maybe it's these different brain locations that contribute to the different class of feelings that each type of deprivation generates. So maybe inner brain deprivations generate the intrinsic or visceral feeling to stop, while outer brain deprivations don't.

Yu-li

- Aug 5, 2011, 7:28p

Hi, I've waited for your post! Your experiment is so interesting. Some ideas come to my mind.

1) You could feel sleepy because of conditioning. The sense of darkness might be associated with sleepiness.

2) You also could feel tired because of mental resource reallocation. (It's a hypothesis). I mean, in some sense, you had depended on visual feedback in order to control your movement. Now you have to decide your movement without some information, so you need to compensate the loss with other types of information. Your body and brain could have been working very hard subconsciously.

3) I think some portion of emotional stability(?) can be explained by decreased quantity of information. I mean, it might not be specific to visual sense. For example, if you cannot smell, you would feel quite indifferent to food.

That's what I think. Good luck!

Archy

- May 12, 2018, 3:47p

Hello Nikhil.

So I was thinking of doing this experiment, and I looked up if someone else has had this crazy thought and I found you.

So basically I was thinking of experimenting because I am studying how visually impaired people face problems while accessing public transport. I thought I should experience it for myself, how difficult it is to reach a bus stop and get on a bus without seeing. Did you come across any such problems?

I know its pretty late, 7 years late to be precise, but do you remember any barriers you came across, even while just walking.

My visual deprivation experiment

Jul 15, 2011, 11:40a - Consciousness

Starting tomorrow, I'm going to start a visual deprivation experiment on myself. For 1 week, I'm going to tape my eyes shut. I'm not going into the lab, and I'm certainly not going to be on the Interweb or reading email. I'm not sure exactly what I'll be doing - I'm guessing trying not to get hit by a car ... more »

Read comments (8) - Comment

neha

- Jul 15, 2011, 9:51a

I was going to ask you if you and Becca wanted to hang out soon. Perhaps the week after.

Niniane

- Jul 15, 2011, 8:28p

Ok this is awesome. I want to hear how it is!!!

Yu-li

- Jul 16, 2011, 1:51p

Sounds interesting! I would like to do the same experiment by myself, but I am too lazy...

I think it is better to measure the effect as objective as possible. How about preparing a color chart so that you can compare the visual perception?

Good luck!

Dylan

- Jul 16, 2011, 2:24p

Good for you. I'm very curious to hear your findings after this. My non-informed guess is you will indeed make it a week, but will spend much of your time just sitting and listening to the radio.

Retsina

- Jul 18, 2011, 7:07a

Very cool, Nikhil :)

Mom

- Jul 25, 2011, 2:53p

Nik - You awesome but crazy kid, you must have begun your experiment by now. I know you will not be reading this blog until you restore your vision. You may look like a raccoon with white circles around your eyes...ha ha.Maybe a visit to the Braille institute will help you read faster and not get bored. Becca can convey my words if she is reading your blog to you.

I look forward to discussing your observation with you...Be careful son.

xoxox

igi

- Jul 29, 2015, 3:53a

where is the result of the eperiment!

nikhil

- Jul 29, 2015, 4:01a

The first day is here

http://superfacts.org/archives/2011/07/visual_deprivat.html

Then use the links at the bottom to go day by day through all 7 days, and then my concluding post.

From physics to perception

Jul 6, 2011, 10:10p - Consciousness

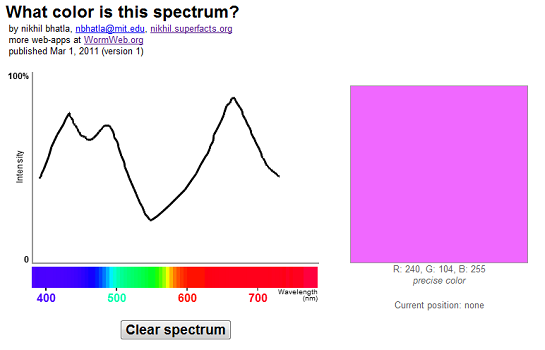

I think the most interesting aspect of consciousness is the phenomenon of qualia, which is what it feels like to experience something (aka "subjective experience"). When philosophers talk about qualia, the canonical example of a quale is the "redness of red".

Color perception in general amazes me. Specifically, I find it astonishing that my eyes and brain can take a ... more »

Read comments (3) - Comment

Namit

- Jul 7, 2011, 11:45a

Is it possible that color perception is a learned phenomena? Just as humans acquire language, which in turn alters their sensory intake, can the perception of color also be something that develops early on?

I understand that linguists argue that language acquisition is facilitated by innate structures in our brain, that no doubt have evolved concurrently with our language systems.

I am curious to know what color perception is like in babies or small children. Maybe they can experience a richer, more continuous spectrum of color than us as they have not yet learned the basic terms that both extend and limit our perception.

The precise color resulting from light of arbitrary wavelengths may indeed be the result of shortcuts taken by our brain on the road to perception, like filling in a missing note of a chord. The spectrum is richer than that which our brains have the ability to perceive, and so it makes a close approximation based on what we're used to.

This comment is much more broad than your above experiment, and one that is weighed heavily by speculation. Still curious though.

Yu-li

- Jul 9, 2011, 8:19p

Hmmm. Qualia is a fascinating subject. I've loved to think about the mistery of qualia, but I have never approached it in physical terms like you. I've tried to discribe it more abstractly(mathematically). Reading your blog post, some ideas came to my mind.

1) I don't know whether the red I see is the red you see. However, red will be used in the real life to induce the same action from both of us. (This idea is kind of behavioralist or later-Wittgensteinish.) We generate the similar output to the same input whatever the internal state is. Data would show the similar pattern if we measure responce time to red letters on green background and red letters on pink background. As the same input generates the same(?) output, we can guess that we share the same/similar internal state(qualia). It cannot be directly proven that we have the same internal state for "red", but it can be indirectly supported. (Even though there are outliers(?) like synesthesia. Their color processing circuit might be different from it of ordinary people.)

2) Colar perception in babies or small children might be hard to study, because they cannot talk well. However, there are studies on blinded adults who had cornea transplanted. Since their color perception is not yet polluted(?) and they can describe what they experience, it is a better approach I think.

3) Taking the evolutionist approach, we can think that "The spectrum is richer than that which our brains have the ability to perceive", because it is not efficient use of mental resource for survival and reproduction to perceive the whole spectrum.

That is what I think.

Paul Science Teacher

- Oct 21, 2015, 5:56p

This is a really nice app. I am interested in teaching about color perception as a collorary to thinking about light spectra, using Benham's Illusion as a trigger for the investigation. Specifically, I am interested in exploring if we can find variations in how people perceive the illusion pattern. Thanks!

A simple argument for the existence of the soul

Jun 18, 2011, 9:55a - Consciousness

(1) I am a conscious being with subjective experience of myself and the world around me.

(2) No theory exists for how consciousness (specifically subjective experience or qualia) can arise purely from physical materials.

If you assume (1) and (2) to be true, one logical result is that

(3) We must live in a world that is not purely materialistic. ... more »

Read comments (13) - Comment

Gokul

- Jun 18, 2011, 11:26a

Hi Nikhil! How on earth is quest for consciousness related to quantum mechanics? like I hear these two things being linked many times.. What is it about? Is it just that we can travel to and fro in time only in our thoughts and memories?

Jason

- Jun 18, 2011, 7:51p

Hey Nik. You may find this documentary interesting. I stumbled upon it recently on Netflix: http://www.quantumactivist.com/

Kate

- Jun 19, 2011, 8:45a

Nikhil, you crack me up. Who knew an argument for the existence for the soul could be so funny and stimulating? Good post.

Here's my comment: while I'm not so familiar with the world of soul-existing arguments, but I think it's a little odd that one of the main tenets of your argument, (2), is that there is no pre-existing theory for X out there.

"(2) No theory exists for how consciousness (specifically subjective experience or qualia) can arise purely from physical materials."

Okay fine... but if there were such a theory (and you didn't like that theory), how would that affect your argument for the existence of the soul? I don't see that it would. Just sayin'...

Keep poking worms.

Neha

- Jun 20, 2011, 10:14a

(c) seems pretty right to me. We're still a long ways off from technology good enough to really get at neurons and what's going on in there! It seems incredibly premature to say that there is no correct theory of consciousness and will never be one. Give materialism a chance!

nikhil

- Jun 26, 2011, 1:50a

To Gokul and Jason, on the topic of quantum mechanics and consciousness:

One central argument against the existence of free will, which is a part of consciousness, is that if we live in a deterministic world governed by the basic rules of physics, there's no room for us to make a "choice". We don't decide what we do, the molecules just follow physical rules and everything is simply predetermined, without another source (free will) influencing things from the outside. So free will is just some sort of elaborate illusion constructed by our brain.

Quantum mechanics changes our notion of determinism in 2 ways. First, fundamental particles become more "random" in that they're position in space seems best described with probabilities rather than definite locations. Second, the act of "observation" (which is not well-defined) forces the particles to adopt definite positions, so an external action seems capable of influencing the outcome of a physical system of particles.

The interpretation that tries to connect consciousness with quantum mechanics builds on each of these ideas. First, because basic particles seem to move probabilistically and indeterministically, perhaps there is now room for free will, because everything isn't just particle-interaction destiny. Second, maybe free will acts as the "observer" and forces the random system of particles to adopt specific positions. This opens the door for free will as an external force that influences and determines reality.

That said, I don't believe anything I wrote in the last paragraph. I think the beliefs around the connection between free will and quantum is 100% hopeful speculation on the part of various New Age thinkers and 0% scientifically supported. Roger Penrose, a famous mathematician/theoretical physicist, put forth the idea that quantum fluctuations in brain cells might support free will, but unfortunately there is zero evidence for this in neuroscience. But of course no one is doing quantum-level experiments in the brain, so it's not like this theory has been proven wrong. It just hasn't been tested, and it just seems highly unlikely given all that's known about how the brain works.

More importantly from my perspective is that the theories above don't address the more basic part of consciousness, what's called the "hard problem" of qualia. Quantum doesn't deal with the question of how we have subjective experience of our world, something that most people intuitively believe is not the case for most other physical objects. What distinguishes our material composition from others' such that it supports qualia, so that we're not just robots behaving like we're alive but we're people actually experiencing life? I've heard no real theory for how qualia can be constructed in purely a materialistic manner, and I don't believe that such a theory can even exist. This is the main reason why I believe in the existence of the soul, or some non-materialist entity that interacts with the material to give materials new properties, such as qualia.

nikhil

- Jun 26, 2011, 2:09a

To Kate, on the topic of materialistic theories of consciousness:

If there was a real theory that explained how consciousness arises from material interactions, I would be super-intrigued. I would be satisfied with such a theory if it enabled me to distinguish conscious objects from nonconscious ones. So it could tell me whether my worms were conscious, or at least what information I'd need to know about my worms to determine whether they were conscious or not.

Based on my original argument above, I would certainly have less logical reason to believe in the existence of the soul.

However, I might still believe, due not to logic but certain life experiences (see http://nikhil.superfacts.org/archives/2008/11/why_i_believe_i.html).

But regardless I'd be stoked.

Yu-li

- Jun 28, 2011, 8:09p

Hi, thank you for another interesting post. As for me, I am an agnostic, but I believe in free will (I often say that "I am determined to believe in free will.") I desperately(?) "want" to believe in non-materialistic soul, but I cannot erase my doubts. I should say I'm still in confusion.

There is a need to distinguish "high-level consciousness" and "lower-level consciousness". Consciousness requires computation, and as you know materialistic theories do exist for computation (like how neural signals are generated and processed). The theories can explain at least lower-level consciousness, and I think worms have very low level consciousness at least.

I would like to quote Marvin Minsky : "we'll show that you can build a mind from many little parts, each mindless by itself. I'll call "Society of Mind" this scheme in which each mind is made of many smaller processes." I think it makes some sense even though I do not like its strong materialistic scent... His approach implies hierarchy of consciousness, and low level consciousness can be materialistic at least.

For high level consciousness (like decision making or construction of theory of mind), I feel a lot of confusion. Emotion is the hardest and most important part, because emotion gives "meaning" to computation. I doubt whether we can perfectly figure out what materialistic processes can generate emotion. However, there are so many other systems(human beings, other animals...) that can generate emotion, and it means emotional systems can be "replicated" in this world. It could imply emotion is also materialistic. I do not believe that there is a clear line between material and mind though (I'm an agnostic).

That is what I think.

Harpoon

- Jul 15, 2011, 7:18p

Hey Nikhil, great topic.

I'm pretty much in agreement with your points. From what I've intuited and read (or rather haven't read) we can't even express theories about consciousness and there's no certainty we ever will. I like Noam Chomsky's succinct comment, "what mind-body problem?" Check out this talk he gave:

http://youtu.be/yJp1-Od67-U

Starts out slow, but he draws some very compelling connections. However this is a follow up to an even better talk he gave previously I believe is called "Linguistics and Philosophy".

I've done some thought experiments on whether consciousness can be divorced from brain. Most of them have gone awry, because I wasn't willing to kill my brain to try it out. The biggest practical joke by consciousness on humans may be the obvious question of what governs the material world. So we could go in the other direction, and ask what I think is a much harder question: what individuates humans from one another, and from other beings, so that they come to call things "consciousness". Which I know sounds similar to the Gaia concept

dullblade

- Aug 30, 2011, 5:53p

I envy your intelligence and your systematic approach to this age-old question. Also you must be a person of great feeling and intuition to arrive at the conclusion that you do; that we do possess "consciousness". Do you believe you can resolve your philosophical question with purely analytical or logical means? Our consciousness is self-evident. That you question it's origin demonstrates the poverty of vision of modern man. We, who have grown up in the age of science, are reluctant to embrace any acknowlegment of our utter incapacity to reach a conclusion about the true mystery and terror of life. You cannot get there from here,( our logic and rational mindset). Godspend to your quest. May you find a way to explain how the divine is manifest in every material part of our wondrous world.

Graham Epp

- Apr 15, 2012, 6:48p

Just accept that conciousness exists without likening it to a soul. If you say a soul exists you lend credibility to magic a.k.a. the supernatural. Some things have reality in the physical plane that will never have a detailed explanation for how they come to be, like free will- and we know free will must exist because people have a share of all available power in the physical plane. My whole point is that lack of a full explanation shouldn't result in a deduction where some might conclude wishing power drives creation.

Anonymous

- Jan 4, 2013, 2:46p

There is a critical thing you are forgetting. Lack of evidence is not evidence in itself. The mere absence of a theory disproving a soul does not state that there is a soul. Take this for example. There is no theory to prove the existence of God. Therefore there is no God. Also the issue of consciousness falls under philosophy not science(although I am sure it will be due to the development of neuroscience and neuro-psychology). It this point we cannot go further than a hypothesis with this issue. If you use the term hypothesis instead of theory it still will not work for you because there are many that do just what premise two claims that theories do not.

Shriram

- Sep 12, 2013, 9:12a

Your arguments are pretty convincing, however we must remember that arguments and counter arguments are always possible with regards to this.

Let me put forth an argument here

1.Existence does not go into non-existence and non-existence does not become existent.

Based on this principle the soul which was not existent did not suddenly become existent. We accept that the person exists currently he cannot go into non-existence.

But then there are many philosophies which say that this soul or consciousness is some thing like continuous motion of something which gives the appearance of continuity like a lamp that can be spinned. Since our consciousness consists of thoughts which are continuously changing we can say that our consciousness is neither existent in the past nor the present nor the future.

We can again argue that without motionlessness motion cannot be defined, the very fact that consciousness can conceive motionless proves this theory to be wrong.

And so on and so forth we can put arguments and counter arguments. There is absolutely no end. If we put an argument forth that the battery has no energy does that mean the energy inside the battery has after life ?

We can put forth another argument stating that even that energy was put into the battery , but how can we say that consciousness is non-existent and suddenly becomes existent.

And so on.

As far as I see certain things are beyond logic, it is the same with consciousness.

John T.

- May 2, 2019, 5:06p

Write (1) ="I am a conscious being with subjective experience of myself and the world around me."

Write P ="consciousness can arise purely from physical materials."

Write (3) = "We must live in a world that is not purely materialistic."

Crucially, the negation of P is distinct from

(2) "no theory exists for how P".

By comparison, in 1500, no theory existed for how magnetism arises from purely naturalistic phenomena. But that has always been true, we just didn't know it.

So, as it stands, (1) and (2) do not imply (3). Indeed, suppose (1) and (2) like you do. This is consistent with there being a true theory that does not yet exist for how P. In that case, (3) is false. So (1) and (2) do not eliminate the possibility of (3) being false.

To Be Conscious in a Body, Frozen

May 16, 2009, 11:21a - Consciousness

It's hard to tell if a thing is conscious. You know, if there is something that it feels like to be that thing. I know it feels like something to be a person, and I think it doesn't feel like anything to be a shoe (unless perhaps I've been smoking some salvia), or to be a dead person. But what ... more »

Read comments (13) - Comment

Tom Stocky

- May 19, 2009, 6:26a

Wow, ingenious is right -- thanks for sharing this.

omar

- May 19, 2009, 9:41p

dear god. this is ingenious, but i am just thinking about this person who is locked in. i think they are likely totally insane. or almost. how could you not be, with no ability to communicate with the world?

when i read the diving bell book, at one point i was reading on the bart. it made me feel so claustrophobic that i almost threw up and had to get off the bart and breathe.

just reading your blog post is making me nauseous.

hope you are well!

Ruggero

- Aug 14, 2009, 3:02p

Is a worm conscious?

nikhil

- Aug 17, 2009, 7:22a

short answer: i don't know whether a worm (e.g. C. elegans) is conscious.

long answer: hmm, what a damn tricky question.

there are a few issues. first, it seems that it is in principle impossible to know if something other than yourself is truly conscious. if you define consciousness to be the phenomenon of having a subjective experience of the world (which is how i use the word most of the time), it seems plausible that another creature could act as if it were conscious even though it had no subjective experience. it would answer your questions, behave "normally", and even say "yeah, i'm conscious", but there may in fact be nothing that it is like to be that creature; in other words, the creature may act as if it has subjective experience without ever having any - it would fake it. and in principle, it seems impossible to know when something might be faking it.

this applies equally to other humans as to other organisms, such as the worm C. elegans. in general, though, when it comes to humans, I seem to make a sort of similarity argument: i'm conscious, and other humans seem to be a lot like me, so they're probably also conscious. so in practice we make assumptions that seem to be consistent with common sense, but in principle confirmation of consciousness in another creature seems unknowable.

second, let's just forget the first problem and say that yes, there exists a behavior that can only exist if a creature is conscious. so if the creature can act in a certain way, then i conclude that it is conscious. which behavior would I use as the test for consciousness? in practice, being able to respond sensibly to questions seems like a nice test, but as in the article above, verbal response seems sufficient but not necessary. also, it doesn't extend very well beyond humans, as we seem to be the only species that has a highly-expressive language (at the very least, we don't have good ways of communicating with other creatures in their own language, if they have one). intuitively, i think my dog is conscious, yet I communicate with her in extremely simple ways. and i can imagine that even if i couldn't communicate at all with my dog, she might still be conscious. my conclusion that my dog is conscious is based largely on empathy and similarity of response - she responds to things (e.g. hunger, anger, treats) in a way that i also respond to those things.

so now on to worms. i have nearly no empathy with worms, and there lives are so different than mine that it's really hard to tell based on intuition alone whether they're conscious. but you can do things in worms that are easier to do than in any other organism: you can identify genes, molecules, cells, and groups of cells that are required for certain behaviors. so if consciousness is due to some physical process (a big assumption), studying worms might be a good way to find pieces involved in that physical process - assuming, of course, that they are conscious (to some degree) to begin with.

i guess this is a very long-winded way of saying that i don't know whether a worm is conscious. there is a specific type of learning that is correlated with awareness in humans (a variant of Pavlovian classical conditioning), and i'm in the process of testing to see whether the worms can do this type of learning. if they can, it would be one small piece of speculative evidence that worms (specifically C. elegans) might be conscious. my hope is that over time we'll discover more behavioral tests that are correlated with consciousness in humans, and that worms could then also be tested. if i accumulate enough pieces of speculative data, the whole argument might become a lot more convincing. that's one strategy, at least.

Ruggero

- Oct 15, 2009, 12:53p

thanks for the very accurate answer.

let's assume that C. elegans is conscious (which i believe is true). is a bacterium conscious? is the fact that a system possesses a neural net that makes it conscious? or isn't just their reaction to a behavioural test? if the reaction makes it conscious then also a bacterium is conscious, since it replies to external stimuli as any other creature. aren't neural nets only there because of the size of the systems and therefore the necessity of a faster communication between parts than that achievable chemically?

nikhil

- Oct 18, 2009, 3:26p

i don't think that just because an organism has a neural net it's also conscious. like i said, i believe you need to find a behavior or some other observable that correlates well with awareness or consciousness. the presence of a neural net could be an example of such an observable, but given that there are many examples of nonconscious states in humans who have neural nets (e.g. vegetative states, dream-less sleep), i don't believe a neural net is sufficient. a neural net may be necessary, as there don't exist any examples of conscious creatures without neural nets, but that is less helpful in identifying those creatures which are conscious.

(as an aside: i prefer using the word "organism" or "creature" over the word "system", as i think "system" masks the complexity found in biology that is not found in standard engineered "systems")

i want to be clear - i don't believe that just any behavioral response is sufficient to show that a creature is conscious. people talk in their sleep and sleepwalk all the time, ostensibly without any consciousness at that moment (or at least very low levels). it's actually pretty interesting to record yourself sleeping - i got a nightvision camera that can do this, and i do all sorts of strange things in my sleep. one night i woke up holding a light bulb in my hand, with no memory of how it got there. the light bulb had been lying on my nightstand, so i just put it back, but it was a bit bizarre...